|

0 Comments

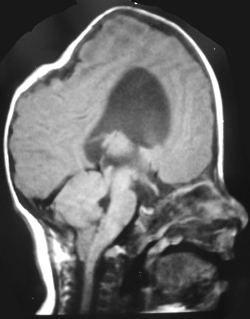

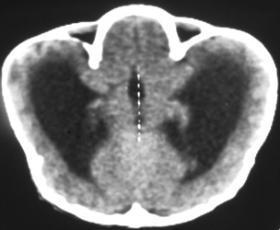

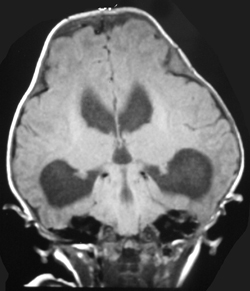

The appearances of the skull of this infant are markedly abnormal. The skull appears to be bulging with multiple overlapping contours. The sutures are abnormally sclerotic and for an infant of this age should not be fused. The MRI and CT images confirm the bulging cortex of the skull vault between the sutures and demonstrate the consequence of this in utero premature craniosynostosis of all sutures, marked hydrocephalus.

The relationship of skull change depends on which sutures are prematurely fused. Most commonly only one suture is involved. Premature fusion of the coronal suture leads to tall (turricephaly) or short AP skulls (brachycephaly, depending on whether you like describing the length or height of your skulls). Premature closure of the sagittal suture has the reverse effect leading to a long AP diameter and reduced height (so called scaphocephaly or dolicocephaly). Premature closure of the metopic suture causes trigoncephaly (forward pointing triangular skull) and plagiocephaly (side-ways skull) refers to the effects after unilateral or asymmetric closure of coronal and lamdoid sutures. Normal width of the major sutures (Coronal, Sagittal and Lambdoid): Birth 10mm 2years 3mm 3years 2mm 30years closed Wormian bones close by 6 months Metopic suture (dividing frontal bone is usually closed by 2 years, but may persist as a normal variant) Craniosynostosis may be primary (idiopathic) or secondary to a variety of endless aetiologies. Along with metabolic profiling and familial genetics, radiology is often central to the determination of the aetiology. Secondary Causes of Craniosynostosis (non-exhaustive) Metabolic (Rickets, Hypercalcaemia (and Hypervitaminosis D), Hyperthyroidism) Haematological (Sickle Cell, Thalassaemia) Dysplasia (Hypophosphatasia, Achondroplasia) Syndromes (Hurler's, Apert's, Crouzon (similar to Apert but no syndactyly), Carpenter Microcephaly (atrophy or dysgenesis) Post-Shunting The chest x-ray appearances demonstrate hyperinflated lung parenchyma with a bilateral upper and mid lung symmetrical diffuse interstitial abnormality. Superficially this resembles a reticular abnormality but if one carefully scrutinizes the periphery of the examination it becomes apparent that there are numerous rings (it is best to review areas between the anterior and posterior ribs so there is no confounding bone overlay). This can be confused for bronchiectasis but if this were the issue one would expect with this severity to see tramlines and some dilatation of the anterior segmental airways of both upper lobes that are usually well seen above both hila.

The differential for a diffuse cystic disease is remarkably short. Excluding emphysema which is not genuinely cystic the considerations are pneumatoceles (usually few/isolated, variable in size and larger), Langerhan’s Cell Histiocytosis (Histiocytosis X), lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) (female and diffuse involvement, not sparing bases, pneumothorax or effusions often present ), tuberous sclerosis (equivalent to LAM), and neurofibromatosis (actually an exotically rare manifestation of this disease, non uniform, larger cysts). The appearances are fairly typical for Langerhan’s with overall lung expansion, symmetrical disease and typical sparing of the bases. These patients are invariably smokers. At HRCT the same distribution is noted with sparing of the anterior medial lung in the bases also evident. Early in the disease small ill-defined nodules are also evident that progressively cavitate into thinner irregular and “bizarrely” shaped cysts. The nodules are usually not visible on CXR. Later in the disease, when the nodules have all resolved and the cysts become confluent, the appearances can be so uniform that it is difficult to differentiate from reticular however, lung volumes are preserved. While the disease is still at least partially nodular significant improvement can occur with smoking cessation. Bone disease is not common in the adult presentation of Langerhan’s as opposed to infant or childhood onset Langerhan’s disease. In this case I concealed the vital piece of the history (trauma). In real life you would usually know that a patient had experienced major trauma. In quizzes and tests of course the rules are different. This is probably because you should always have your mind open to the possibility of prior trauma as the patient may be unwilling to reveal the history for legal or domestic reasons and there may be elements of lesser trauma that you were not informed of (iatrogenic biopsies etc).

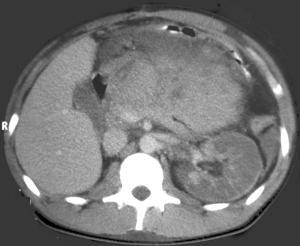

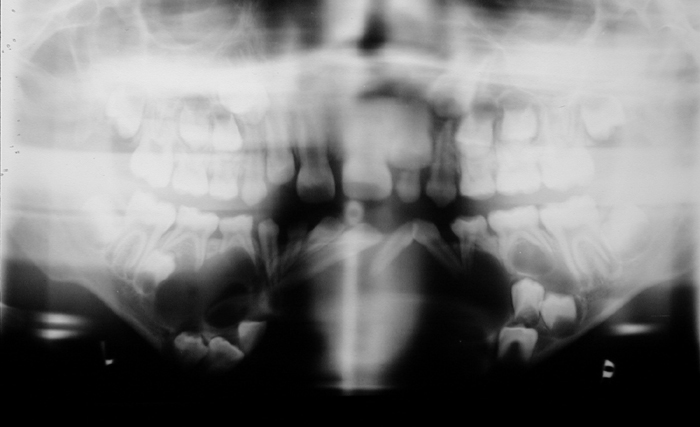

This case demonstrates a kidney with impaired perfusion. There is only preservation of capsular perfusion that originates from smaller vessels, suggesting arterial disruption. Venous infarction usually results in persistent cortico-medullary differentiation. Contrast in the collecting system is always absent in arterial pedicle avulsion but may be present in venous thrombosis. The kidney is a little large, which may occur in arterial or venous infarction, however, in this case this was likely pre-existant as the patient had congenital absence of the right kidney. There is also a large anterior abdominal soft tissue mass. This is heterogeneously dense prompting many to think this was an enhancing mass, possibly pancreatic neoplasm or pancreatitic phlegmon.This mass does not enhance, but was actually hyperdense pre-contrast due to mesenteric haematoma. There is also hyperdense fluid in the left paracolic gutter from haemoperitoneum. In combination the renal findings are best explained by traumatic disruption of the renal artery pedicle which is probably the commonest causes of acute renal infarction of a whole kidney. Non-traumatic arterial renal infarction may also result from embolism, for example from atrial thrombus or valve vegetations, however, subtotal infarction is commoner and there are usually features of embolic disease in other organs like the spleen. Other explanations include traumatic intimal damage from renal arteriography, or thrombosis of the renal artery related to atherosclerosis, aneurysm or dissection of the aorta and vasculitides. The presence of a capsular rim of enhancement does not imply the kidney is unsalvageable, although clearly the prognosis is poor. The image in this case demonstrates the orthopantomogram of a young child. The orientation of the teeth is a mess! This is even more so than would be expected by the numerous unerupted and extra teeth present. The unerupted teeth of course indicate that the patient is a child, however, in addition to the haphazard arrangement in both the maxilla and mandible the teeth are also associated with numerous cysts. Unerupted teeth are usually associated with a small cystic covering but this is more than would be expected as the cysts are quite large in cases. The cystic lesions are well-defined peripherally with no obvious erosion. Notably, most cysts appear related to the crown of unerupted teeth. The findings are highly suggestive of dentigerous cysts. The presence of multiple mandibular or maxillary cysts, in particular dentigerous cysts, is highly suggestive of Gorlin's syndrome.

Some may confuse this appearance with ameloblastoma. Ameloblastoma is usually a solitary multiloculated soap bubble type lesion that typically is located at the angle of the mandible. The lesion is frequently associated with resorption of adjacent roots as it is a locally aggressive lesion. Similarly, eosinophilic granuloma may cause tooth root resorption and the classically described “floating teeth” appearance. The possibility of cleidocranial dysostosis is a significant consideration in view of extranumarry teeth. However, the presence of multiple cysts is atypical. Additionally, other features that might be present such as midline failure of fusion of the mandible or maxilla are not demonstrated in this case. Remember, of course that orthopantomograms are often “fuzzy” in the midline. This is a difficult but characteristic (Aunt Minnie) type of diagnosis. Hopefully, once seen this is not forgotten. Please remember that there are associations in Gorlin's syndrome that might include basal cell naevi and intracranial calcifications. This case is tricky case but boils down to basic radiological interpretation of lesion characteristics. Any lesion can be analyzed in terms of size, shape, contours, location and density. The latter two of these features allow us to characterize these lesions and arrive at the correct diagnosis.

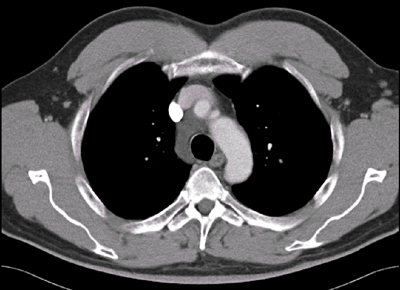

There is no pulmonary embolus (is there ever?!). There are lesions in the liver (multiple other lesions were present), nodes at the right hilum and multiple lesions in the lungs. All of the lesions demonstrate similar constituent densities. There are large areas in almost all lesions of macroscopic fat. The lesion in the liver does look very aggressive prompting thoughts this may be a hepatocellular carcinoma. Indeed HCC and adenomas in the liver may have fat within them. However, it would be extremely unusual for all the metastatic lesions from a HCC to contain so much fat. Other solid lesions that may contain fat might also include germ cell tumours and sarcomas (particularly liposarcoma). Other rarer lesions include angiomyolipomas and deposits in Gauchers disease, however as we will see these do not fit with the pulmonary appearances. The pulmonary lesions are variable. Several lesions - like the lesions in the left upper lobe and the left lower lobe appear discrete and consistent with intrapulmonary metastases. However, others however appear more unusual like the tubular lesion in the posterior segment of the right upper lobe. This lesion is fat containing just like the other lesions. The possibilities for this lesion might include an endovascular or endobronchial abnormality. The presence of small buds on the side of this tubular opacity and of other clustered nodules in other areas of the lungs suggests endobronchial disease spread. There are limited causes of multiple peripheral endobronchial lesions. These might include polyposis, granulomas (tuberculous or sarcoid), carcinoids, and metastatic lesions from renal cell, melanoma, breast and sarcomas. Of these only sarcomas are fat containing. Therefore, the only diagnosis that optimally fits is metastatic liposarcoma - conveniently the correct response! Teaching Point: Remember to always look at a lesion in terms of size, shape, contours, location and density. |

From Grayscale

Latest news about Grayscale Courses, Cases to Ponder and other info Categories

All

Archives

October 2018

|

|

|

Grayscale Courses est. 2015

RSS Feed

RSS Feed