|

2 Comments

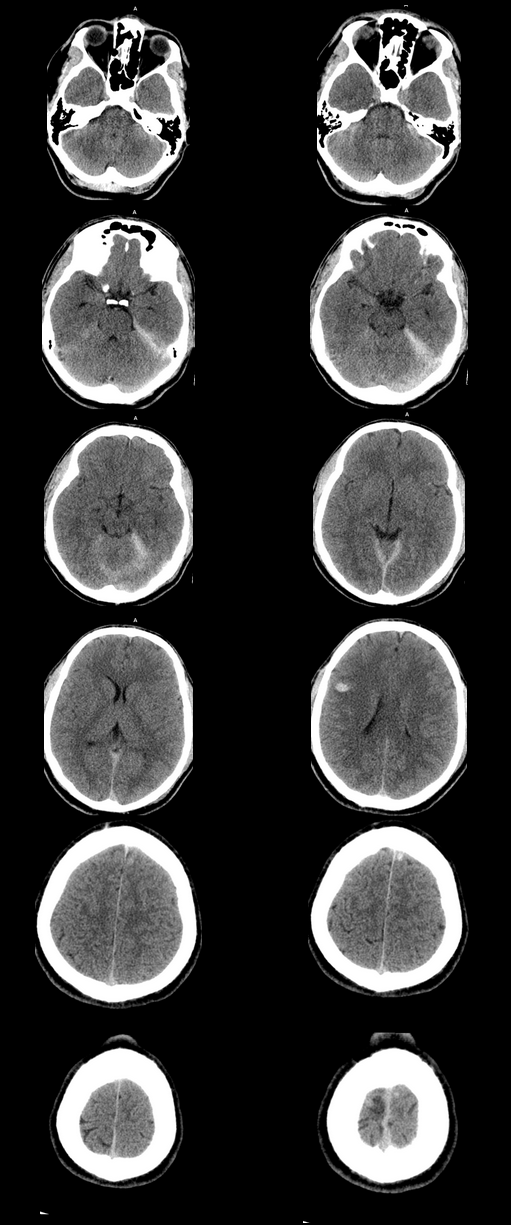

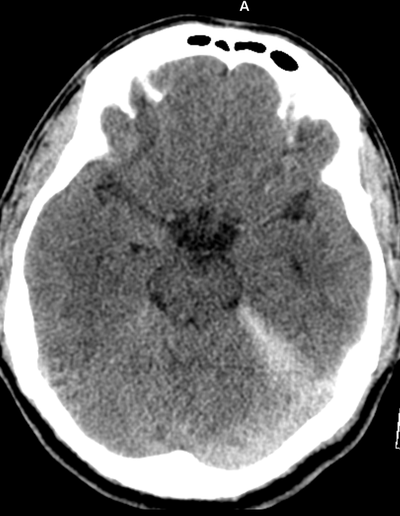

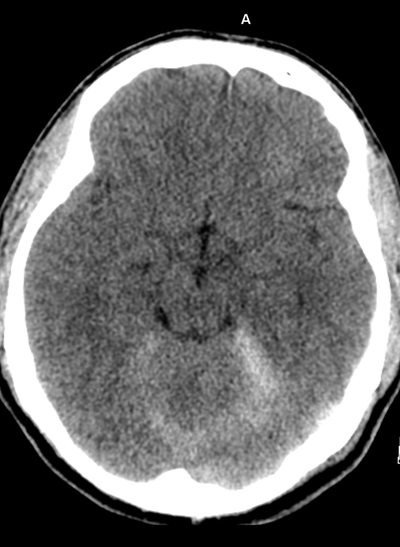

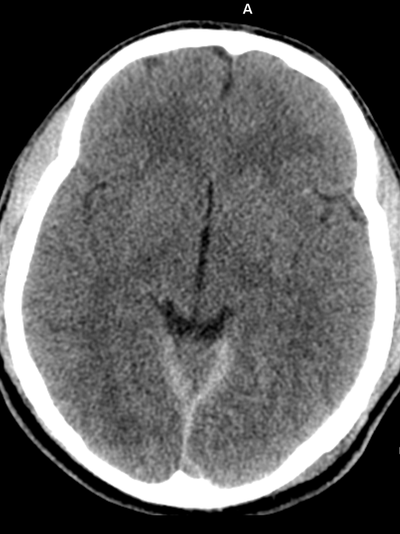

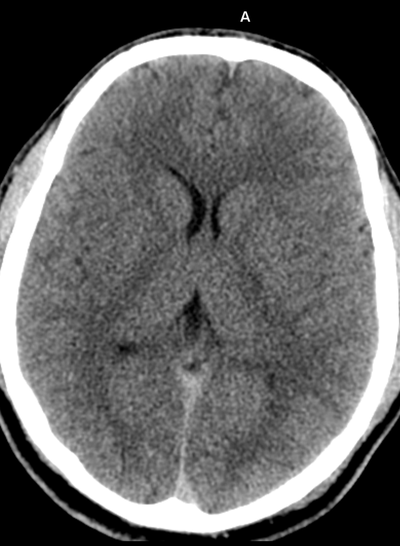

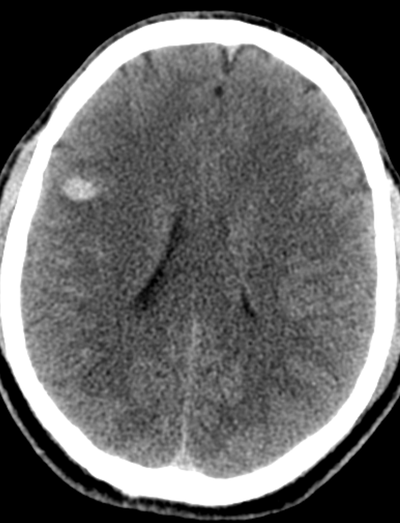

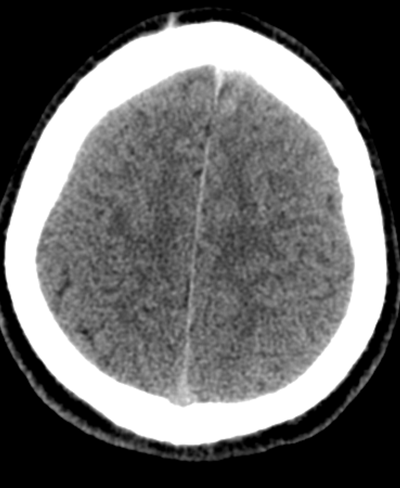

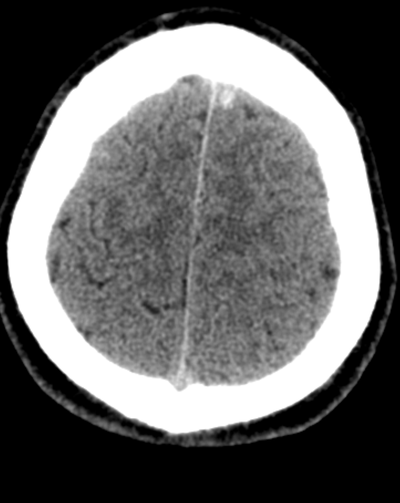

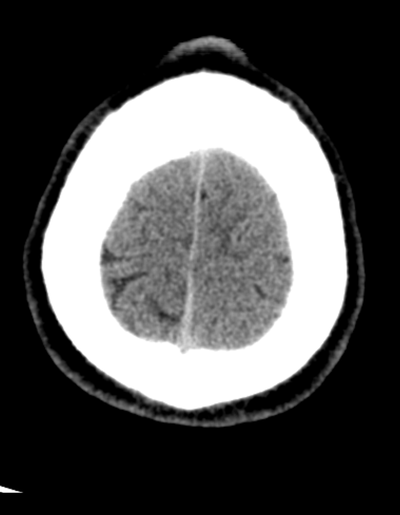

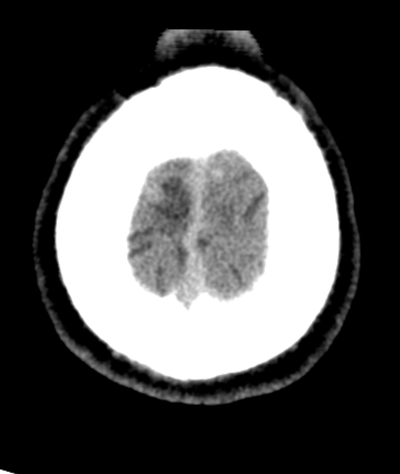

Case to Ponder 79 Answer: Acute subdural, petechial haemorrhages and early diffuse axonal injury29/1/2017 Radiology Level: FRCR, FRCS, MRCP, ABR, EDiR, Radiology Mid-Level ++ The appearances here are of a severe intracranial injury.

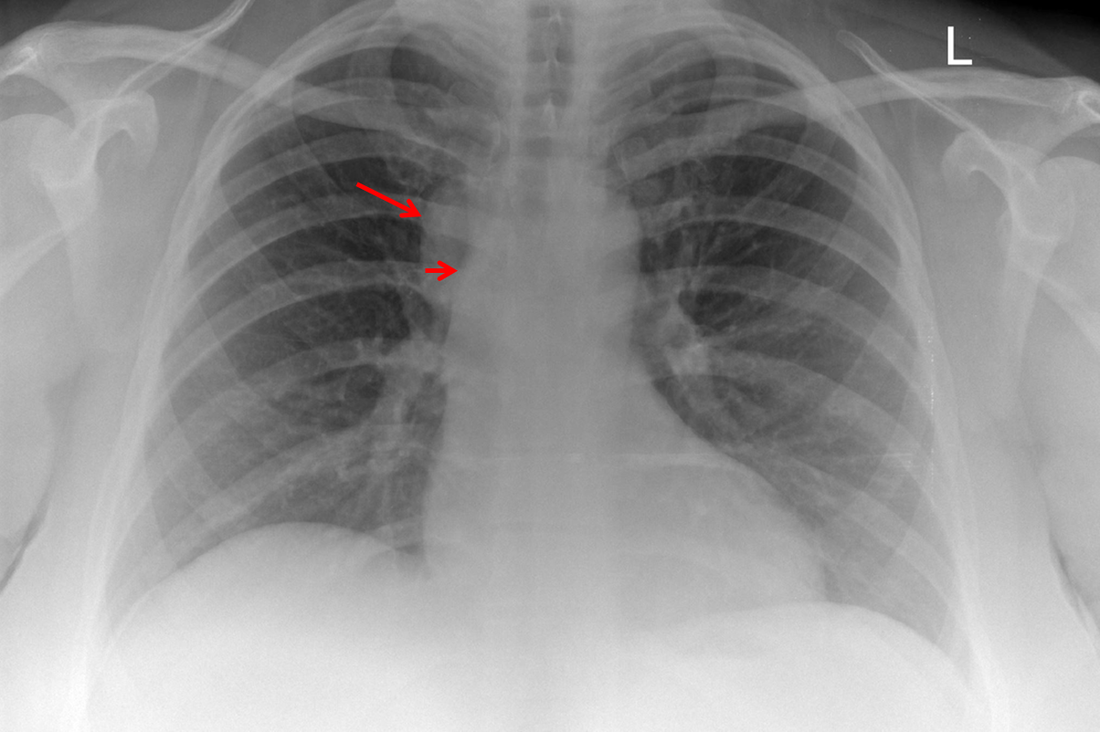

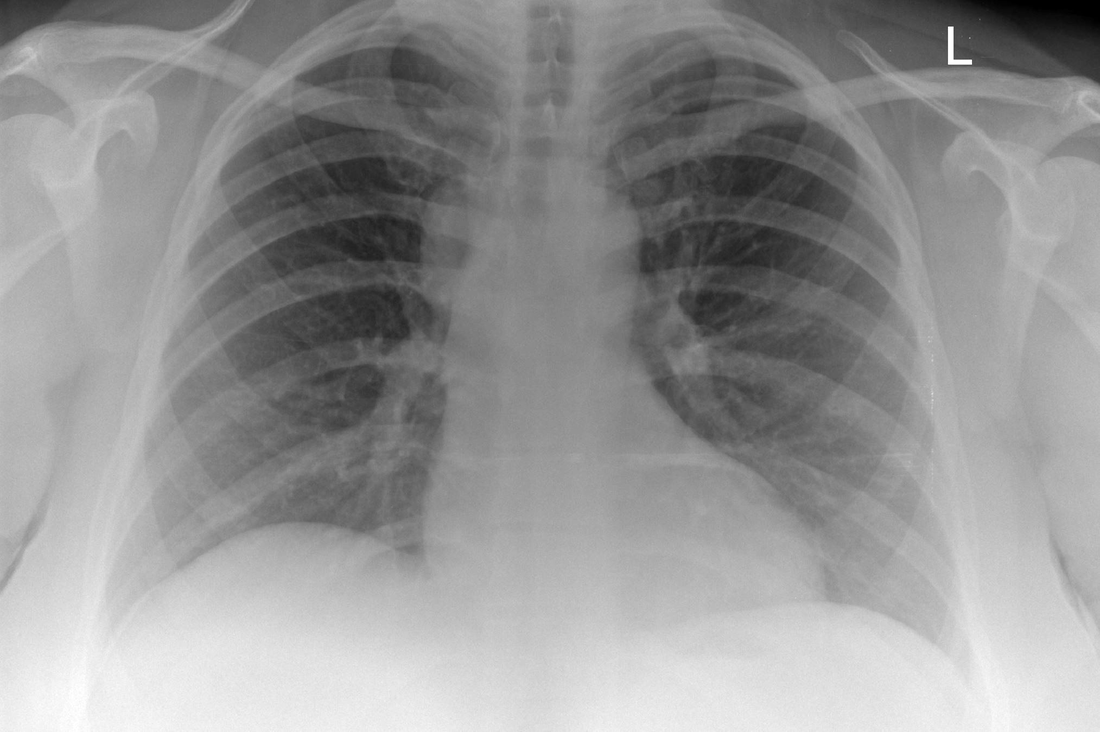

Radiology Level: FRCR, ABR, EDiR, MRCP, Radiology mid-level ++ The original chest x-ray demonstrates a large hemispherical opacity lateral to the right superior mediastinal border with a well defined lateral margin (long narrow). Assuming that most lesions are roughly spherical, it is therefore most likely to reflect a mediastinal lesion. It is important to recognise that there is no widening of the right paratracheal stripe. This right paratracheal stripe can still be observed extending along the inferior margin of the right tracheal border, extending to the tracheobronchial angle measuring no more than the upper limits of 5mm (short arrow). This implies that the lesion is not in the anterior mediastinum and must lie in the middle or posterior mediastinum. The for dislocation the finding is unlikely to reflect adenopathy or mass, for example due to lymphoma or other anterosuperior mediastinal mass.

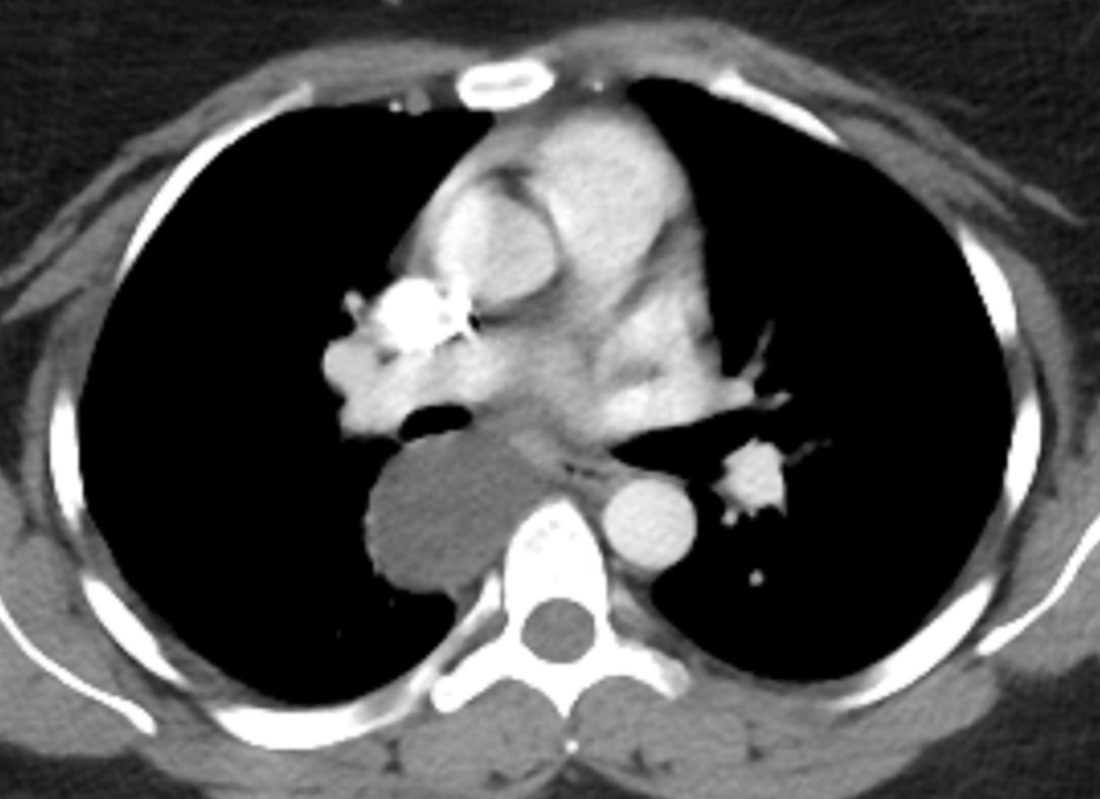

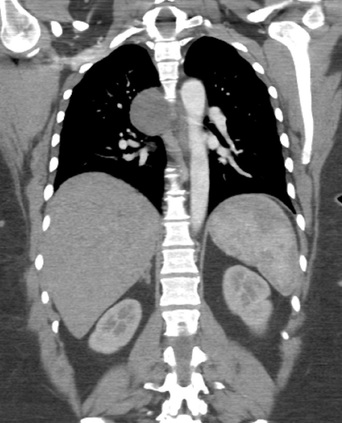

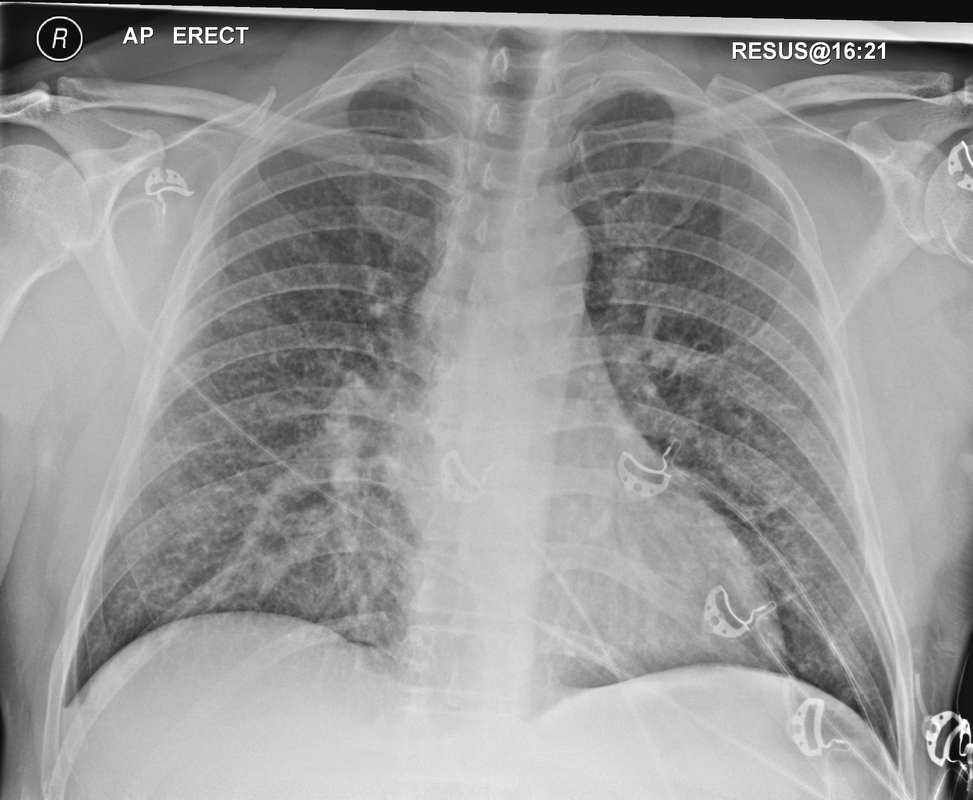

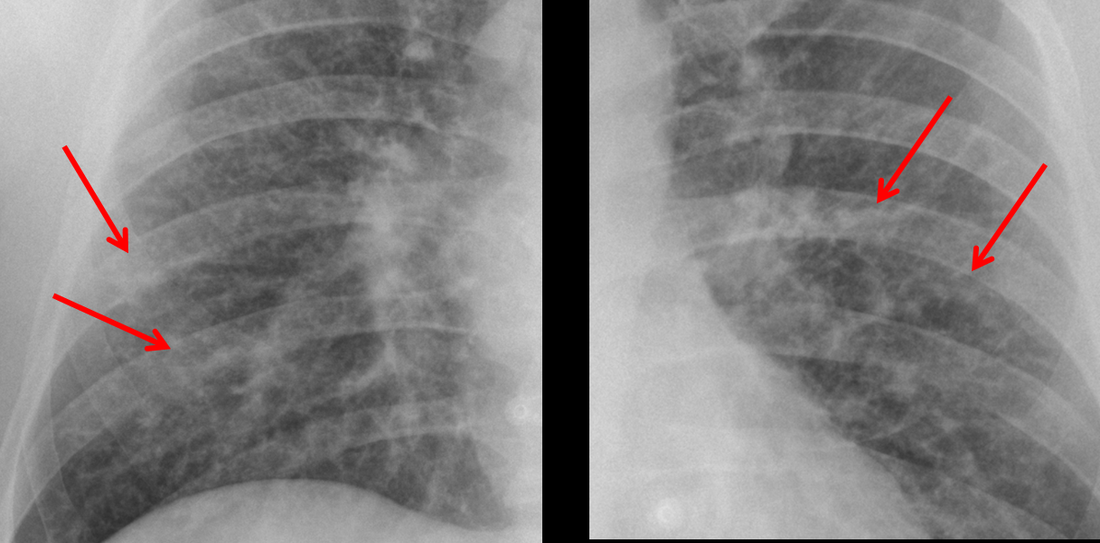

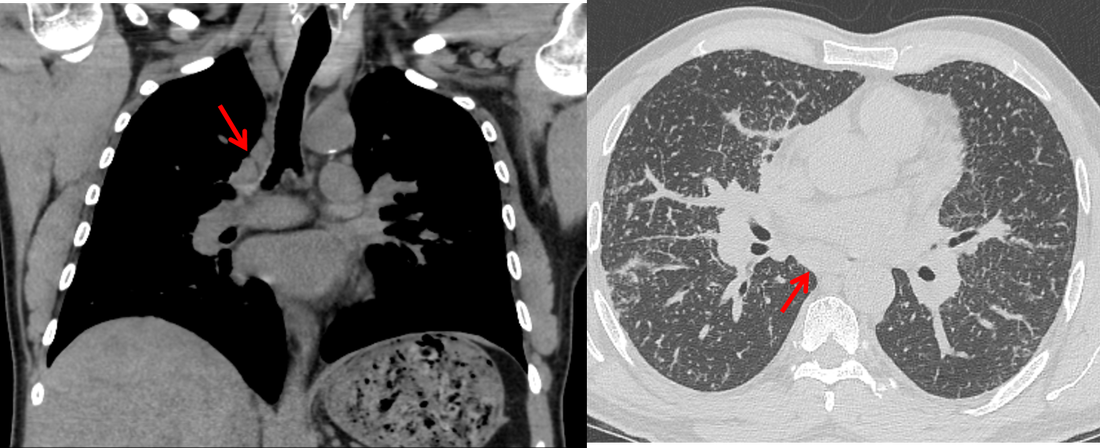

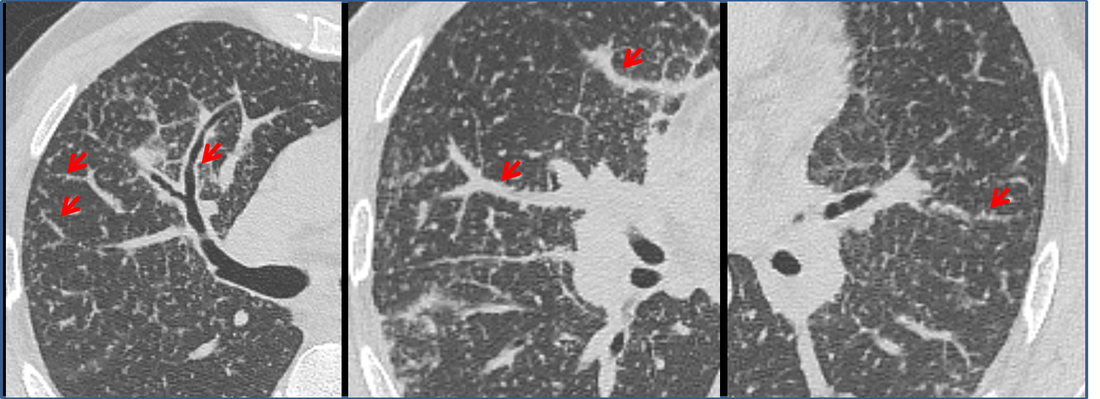

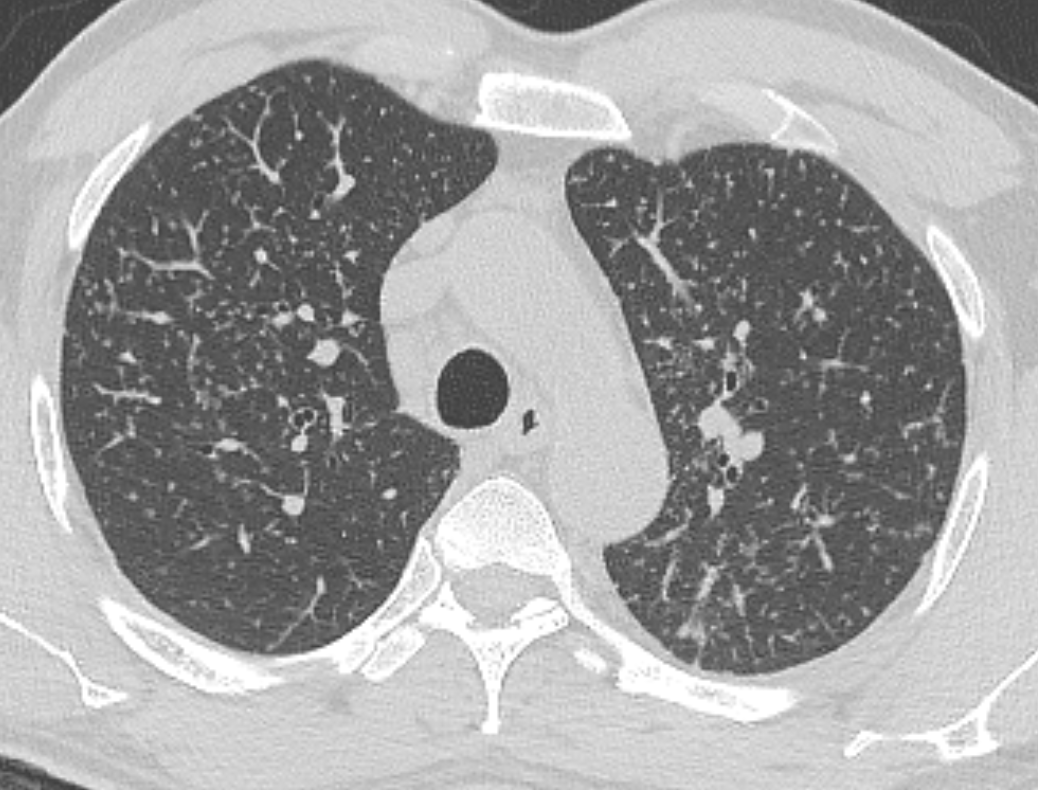

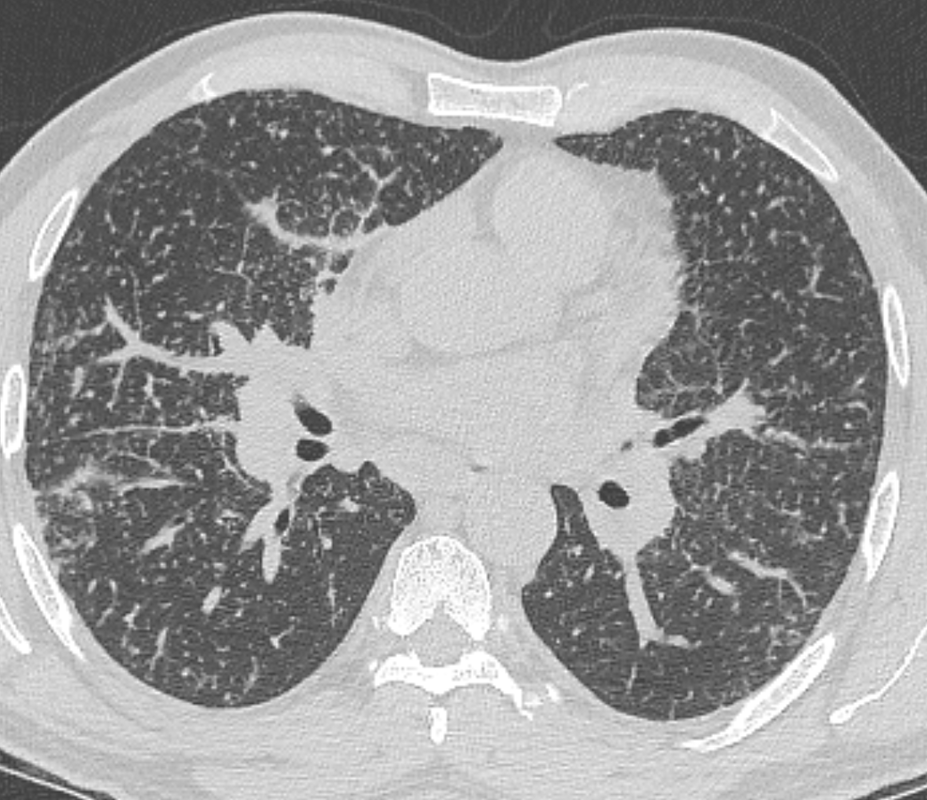

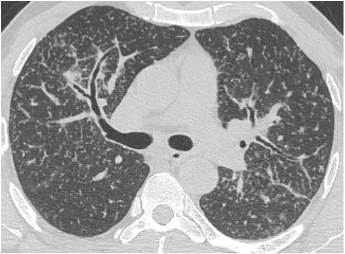

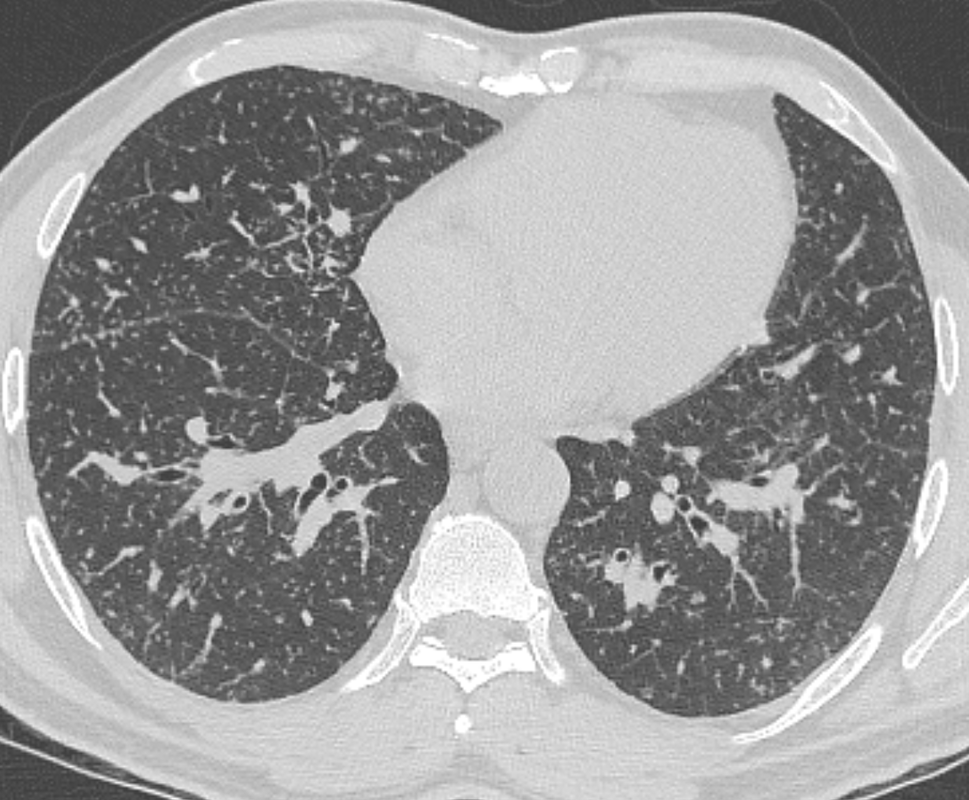

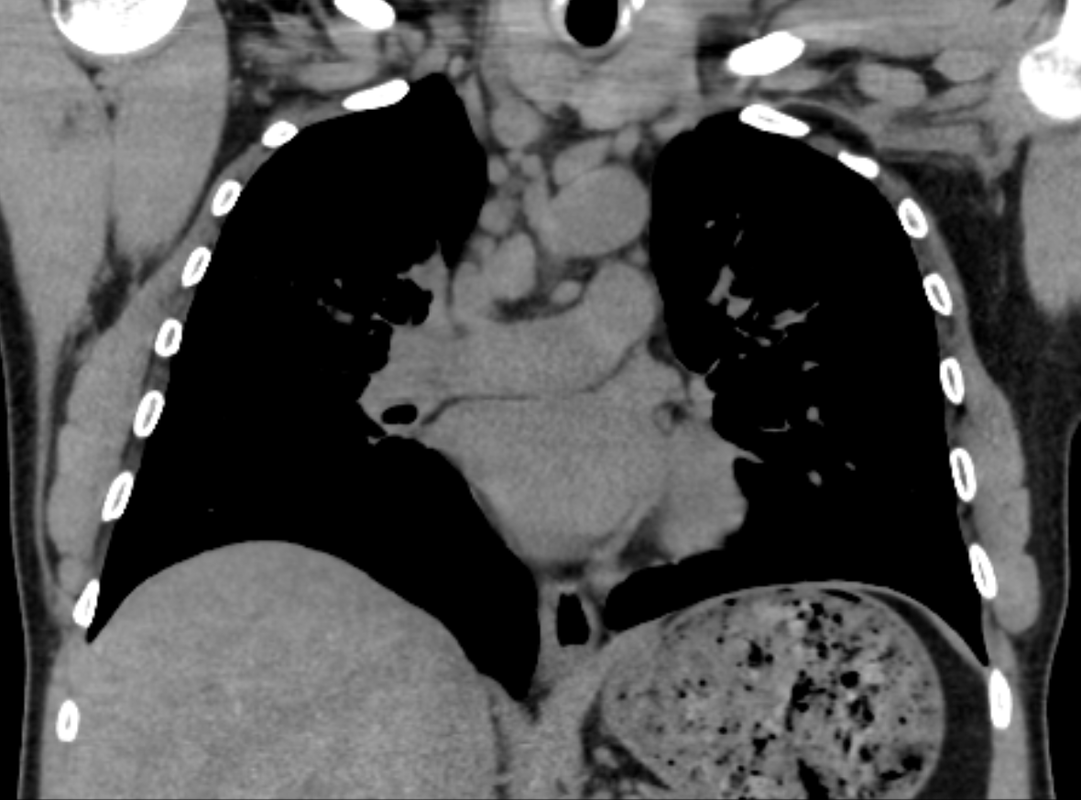

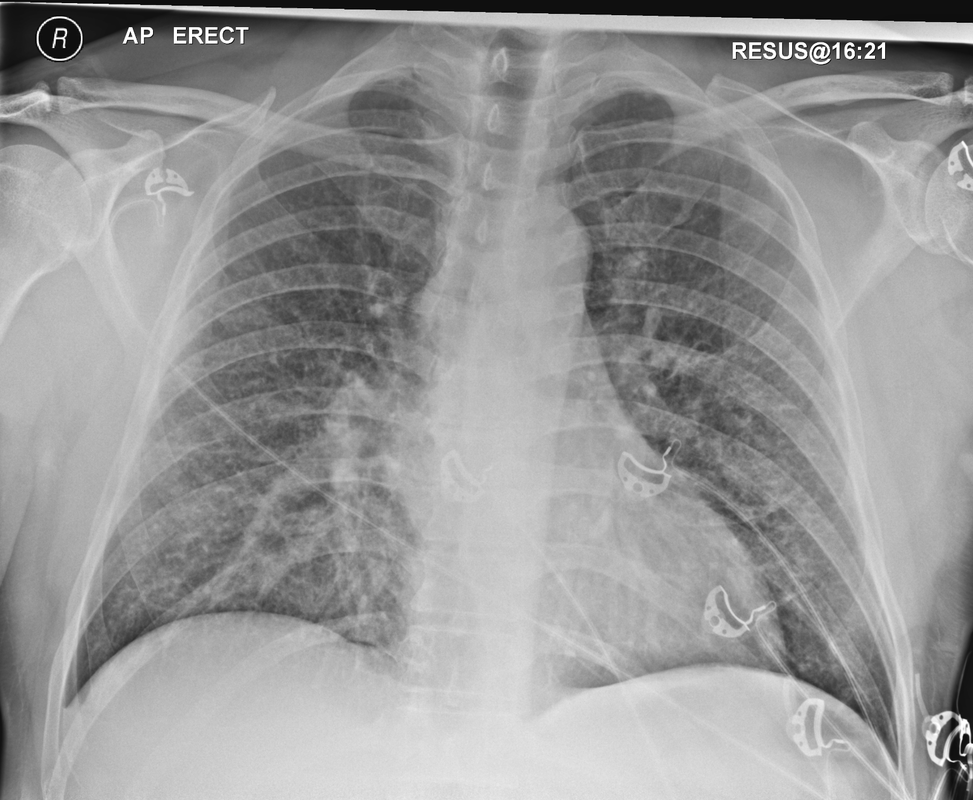

The CT images confirm that there is a mediastinal abnormality that is well defined, homogeneous and of unform relatively low density, less than solid.The abnormality is unilocular and single. The abnormality lies in the middle/posterior mediastinum and as can be confirmed on the coronal reconstructions is separate from the trachea. Hence there is no silhouette sign, with no loss or widening of the right paratracheal stripe. These appearances are diagnostic of a bronchogenic cyst, also referred to as a foregut duplication cyst. These lesions are very common in this location and more typically right-sided, extending into the azygo-oesophageal region as in this case. Although the density of the abnormality is frequently fluid, the abnormalities may be slightly hyperdense, indicating a slightly proteinaceous contents. Similarly on MRI it is in my experience more typical to see mild T1 hyperintensity rather than the typical low T1 signal characteristics often described. No enhancement is noted within the abnormality on CT or MRI although occasionally mild enhancement of the wall of the cyst can be demonstrated. Most bronchogenic cysts are asymptomatic discoveries and often measure as much as 10 cm at presentation. Surgery is indicated for comparison symptomatology which is unusual. Secondary infection can be an occasional cause for presentation. The diagnosis should be suspected on plain films where there is a well-defined lesion in a roughly spherical configuration particularly in the middle/posterior mediastinum near the carina. Radiology Level: FRCR, ABR, EDiR, MRCP, Radiology Mid-Level++ Initial Radiograph The initial AP erect radiograph is covered in ECG leads. This indicates that the patient is unwell, an important factor when considering the causes of abnormality on a chest radiograph. The film demonstrates prominence of the central vasculature, with indistinctness of the central bronchovascular structures and linear markings extending from the hilum. The features suggest interstitial oedema. The upper lobe vasculature is not particularly prominent and the heart is not markedly enlarged, however, these are features of chronic pulmonary venous hypertension. This patient is young and so unlikely to as yet to have developed these features. At aged 35 atrial fibrillation is unusual and the likely cause of interstitial oedema. 2 week follow-up The follow up radiograph is following two weeks of therapy. The ECG leads are gone and the patient was better, clinically out of interstitial oedema. It is tempting to think that the chest radiograph is now normal, or at best suggests some reticular linear opacities radiating from the hilum that may suggest some residual interstitial oedema sequelae. But look more closely at the film, particularly in the mid zones. There are additional nodules present. Indeed these are superimposed over the linear reticular markings so this appearance is what we would call reticulonodular. Look at the lateral margin of the horizontal fissure and some of the larger and smaller vessels, they appear beaded due to adjacent nodules (long arrows). Determining whether an interstitial process is nodular (e.g. miliary), reticular (e.g. fibrotic or oedema) or reticulonodular is critical to determining the cause of pathology and does take some experience. If you saw the nodules but thought this might be miliary nodules in an Asian patient (i.e. perhaps TB), not bad, but miliary is a haematogenous process and should be worst at the bases. For trainees, especially in exams, this is stressful and it is a common situation for trainees to plump for reticulonodular as a compromise where they feel they are not going to be too wrong either way. This is a bad approach. Determining whether the disease is one of these three options helps you to determine the cause. Don’t chicken out of making that decision! In this case reticulonodular meant to me when I was reporting these plain films that I was effectively down to only 2-3 diagnoses, which we will come to. What else on the second chest radiograph? Well the right paratracheal stripe is widened at its inferior margin and the right superior retrocardiac region where the azygo-esophageal stripe should be visible is widened (short arrows). In the tracheobronchial groove the right paratracheal widening could be due to a prominent azygos due to fluid overload/oedema, but the right retrocardiac/azygoesopahageal widening confirmed adenopathy. I was now down to effective one diagnosis. I didn’t have old reference films so I requested a CT with HRCT imaging to confirm my suspicion. Select annotated images from original provided CT set The CT examination was performed a couple of weeks later. It confirms the presence of adenopathy in the right paratracheal region and the azygo-esophageal region (short arrows). Note how on the coronal images the right paratracheal region is widened and causes the chest radiograph appearances. Selected annotated images from the original provided CT set What about the lung parenchyma? There are numerous small nodules present, measuring 2-3mm in size at CT. This is a micronodular appearance. To evaluate this, my first question is whether they contact the fissures or the pleural surfaces. Look at the beading of the major fissures, clearly they do. This means the nodules are lymphohaematogenous and not centrilobular. Now let us examine further. The next question to consider is whether the nodules are diffuse and distributed randomly (i.e. miliary) or whether they are more clustered around the central vessels and airways (the so called axial interstitium) and the fissures/pleural edges. In this case it might be tempted to think that the nodules are everywhere, they must be random. But look carefully at how thickened the central airways are. Look at the fuzzy nodular appearance of the central airways and vessels extending to the periphery. These are studded with innumerable small nodules. Even where nodules appear “random” in the middle of the lung, they are actually lining vessels or airways. This distribution of nodules along vessels, airways, pleura and the fissures is termed a perilymphatic distribution and corresponds to rerticulonodular at plain radiograph interpretation. I am now only considering three diagnoses: sarcoidosis (and its mimic silicosis in appropriate occupational exposure) and lymphangitis carcinomatosa.

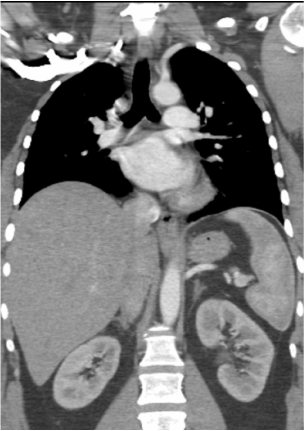

How do I narrow it down? Well lymphangitis is more often unilateral or asymmetric. Interlobular septal thickening is far more common, effusions are very common. Neither are present in this case. So I am left with sarcoidosis or silicosis. I could go and find out if the patient had an occupational exposure, but I am a radiologist and need to push the diagnosis from imaging and clinical knowledge. Firstly silicosis is increasingly rare unless I am in a mining/sandblasting community. Nodes are more likely to calcify in silicosis, although could be non-calcified in both entities. But more importantly this person presented with atrial fibrillation with interstitial oedema at a young age. Silicosis does not cause cardiac disease. Sarcoidosis itself does not usually result in effusions. However, when in sarcoidosis you see evidence of arrhythmia, effusions or oedema, always think about the subset of sarcoid patients who have additional cardiac sarcoid. The diagnosis in this case was indeed sarcoidosis with pleuroparenchymal and cardiac involvement. I made the diagnosis based on the two chest x-rays but it was academically gratifying to follow through to see the CT imaging and make an illustrative teaching case. Maybe at another time we will look at the next investigation that should follow, a cardiac MRI to confirm myocardial sarcoidosis. The initial chest radiograph demonstrates an abnormal opacity in the right inferior hemithorax. This demonstrates a parallel orientated opacity to the right hemidiaphragm, with some very medial loss of visualisation of the right hemidiaphragm. The abnormality is not anatomically suggestive of a parenchymal abnormality and has vessels seen to be coursing through it, further supporting this is not likely due to a parenchymal air space opacity. There is no blunting of the right costophrenic angle to suggest this is loculated pleural fluid elsewhere. The left hemithorax is clear and the cardiomediastinum a little distorted by a mild scoliosis but otherwise unremarkable. It is noted that there are old posterior fractures of the right ninth and tenth ribs.

The CT examination is illuminating. This demonstrates no overt pleuroparenchymal abnormality. There is elevation of the anterior aspect of the right liver lobe with a notched appearance to the lateral margin of the liver on the bottom left image. Also noted is that there is low attenuation along the vessels in the anterior segment of liver. This suggests that there is segmental mild biliary obstruction in this region, but not centrally in the porta hepatis. The remainder of the right posterior liver and left liver lobe are unremarkable. The right lateral margin of the liver in contact with the right lateral chest wall has lost its normal rounded configuration and has a squared off appearance. These appearances are indicative of a right diaphragmatic traumatic injury with partial herniation of the liver through the diaphragmatic tear. This results in the notch in the lateral liver aspect as well as the segmental ductal obstruction of the herniating segments. Diaphragmatic tearss are not uncommonly delayed presentations following trauma. In part this may because patients with trauma may be treated with positive pressure ventilation which may suppress a diaphragmatic injury. But also tears can enlarge with time becoming sympomatic. Diaphragmatic injuries are commoner on the left side and less so on the right side, thought to be due to the protective of the liver. Most commonly these are due to increased intra-abdominal pressure from blunt injury but can also of course occur with penetrating injuries. Delayed diagnosis results in increased morbidity and mortality, particularly as larger hernias can become more difficult to surgically repair. CT is essential in confirming the diagnosis of diaphragmatic tears, particularly the coronal and sagittal reconstructions, although these are less helpful on the right side due to close approximation of the liver to the diaphragmatic fibres, frequently with no substantial interposing fat. This case was diagnosed based on the abnormal configuration of the right diaphragm with evidence of prior trauma (rib fractures), aided by the focal biliary tract obstruction. Such cases should be differentiated from diaphragmatic eventration which is due to an anteromedial weakness of the diaphragm. In this context the PA chest x-ray would demonstrate loss of the entirety of the right cardiac border near the elevated segment and there would be no evidence of biliary obstruction present. |

From Grayscale

Latest news about Grayscale Courses, Cases to Ponder and other info Categories

All

Archives

October 2018

|

|

|

Grayscale Courses est. 2015

RSS Feed

RSS Feed