|

2 Comments

Radiology Level: FRCR, FRCS, MRCP, ABR, EDiR, Radiology Senior +++

An interesting case to analyse. The abdominal radiograph demonstrates extensive areas of intrabdominal calcification. These do not conform to any intrabdominal organ, nor the bowel to suggest bowel contents. Therefore, these findings are likely peritoneal in nature. There are not many causes of peritoneal calcification. Intuitively, tuberculosis and peritoneal mesothelioma may come to mind. However, in the former calcification is unusual and limited and localised when present. Calcification is even rarer within peritoneal mesothelioma even if pleural plaques are calcified in the same patient. So it is important to consider other conditions. Pseudomyxoma peritonei can be associated with small areas of focal punctate or linear calcification. In these cases the bowel would be expected to be centrally displaced by the gelatinous soft tissue filling the peritoneum. This is not present in this case. Two conditions should be considered with extensive calcifications of this type. These are psammomatous calcifications in ovarian malignancy and the calcifications of sclerosing peritonitis. These two types of calcifications can be differentiated by their morphology. Psammoma bodies are usually fluffy calcifications that appear almost to be forming ossified bodies. In distinction the calcfications of sclerosing peritonitis are usually linear or sheet like. Therefore, in this case the calcifications are typical of sclerosing (or encapsulated) peritonitis. This is a calcification pattern that develops in patients on peritoneal dialysis. The appearances are often referred to as a "cocoon abdomen". The presence of the calcifications and peritoneal loculations impairs the ability to perform peritoneal dialysis effectively by reducing the peritoneal surface accessible to the dialysate fluid. When identifying features of one disease it is also important to look for further features that may corroborate the process. What about the bones, are they normal? The bone density is diffusely increased, the trabeculae are ill-defined, there is alternate sclerosis and lucency of the vertebral bodies ("rugger jersey spine"). These are features of renal osteodystrophy. The sacro-iliac joints are also ill-defined and widened. This is a feature of the hyperparathyroidism component of renal osteodystrophy resulting in subperiosteal bone resorption. Finally, vascular calcifications are present. These are less specific and seen not only in renal impairment but also in diabetes and elderly patients with atherosclerosis. The surgical clips in the pelvis are not related to a prior transplant as suggested by some, but rather due to sterilisation clips. Unrelated clips in the upper abdomen are due to unrelated surgery. Always look at all elements of a case. The bones, the soft tissues, the gas pattern, they may all assist in confirming a diagnosis and finding all its manifestations. Radiology Level: FRCR, FRCS, MRCP, ABR, EDiR, Radiology Senior +++

Ignore upper abdominal surgical clips. Radiology Level: FRCR, FRCS, MRCP, ABR, EDiR, Radiology Challenge ++++

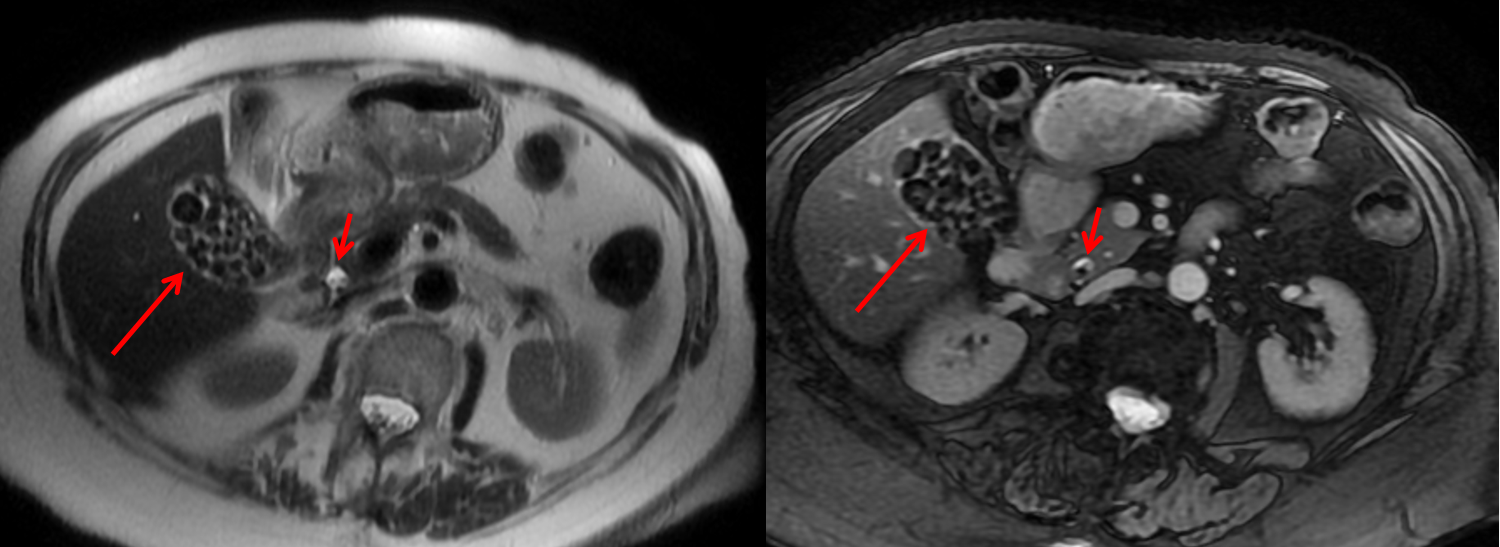

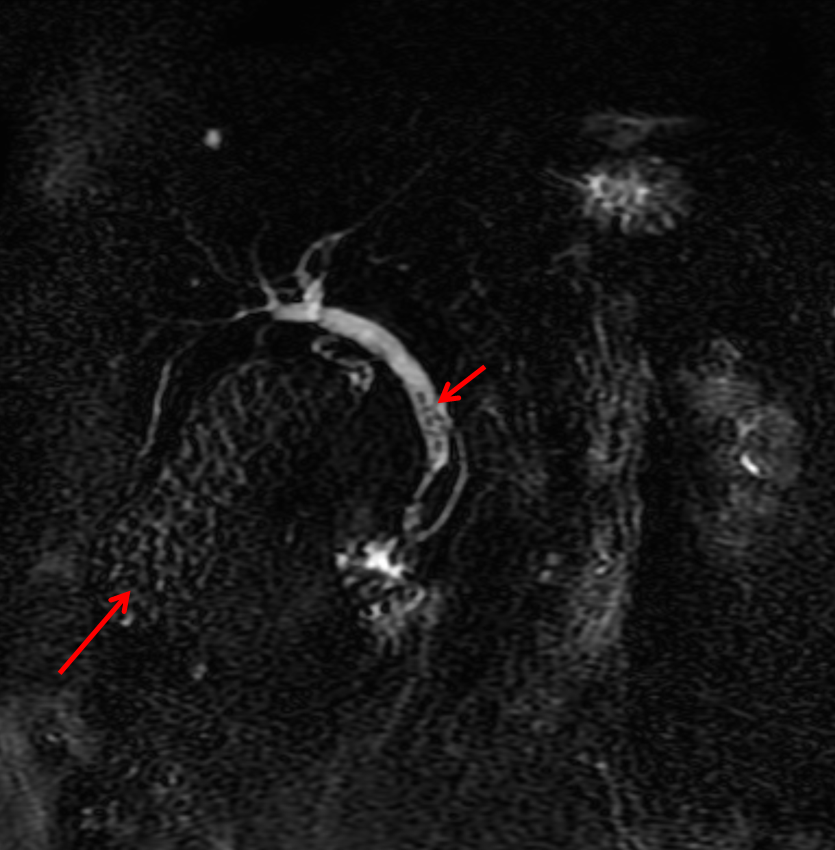

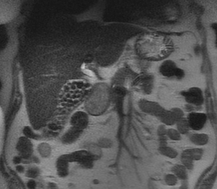

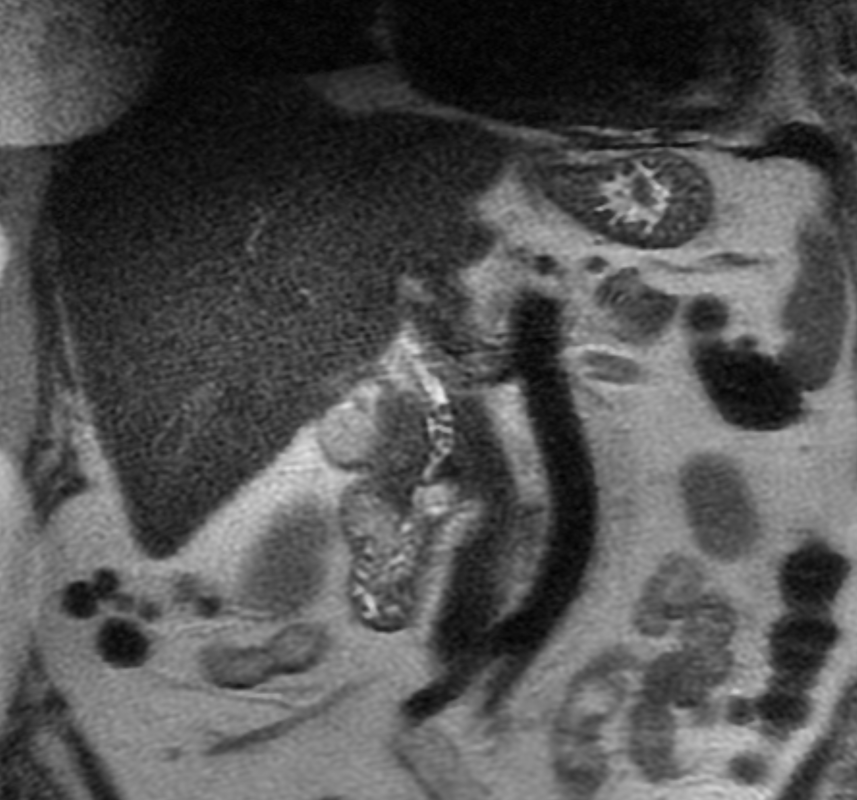

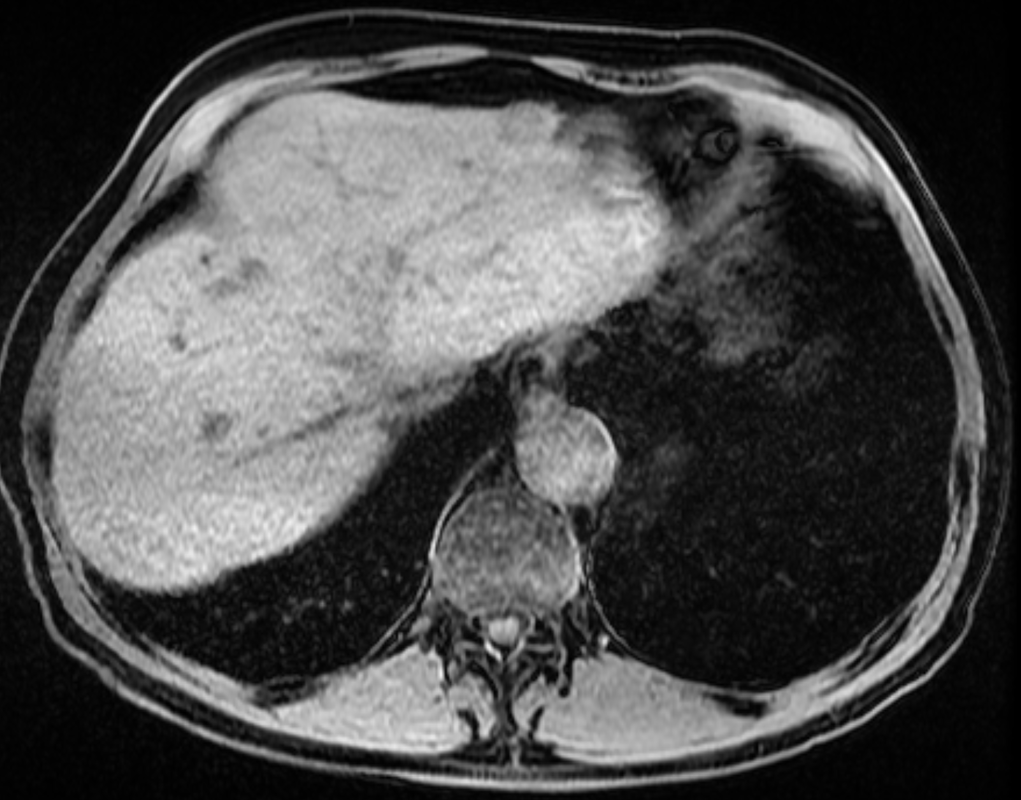

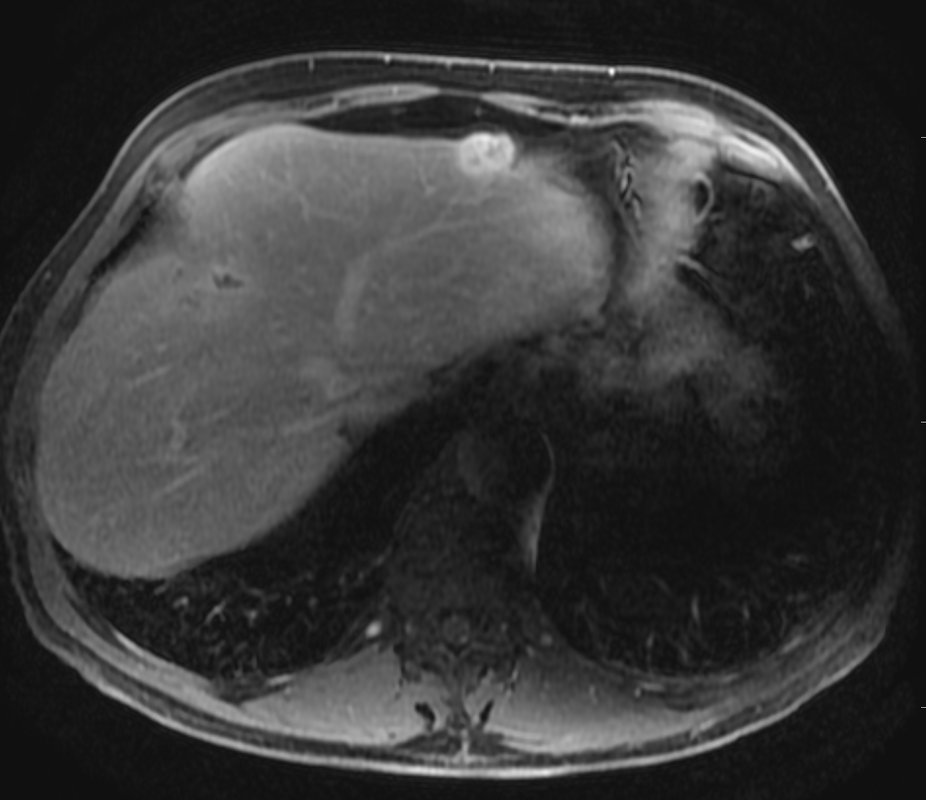

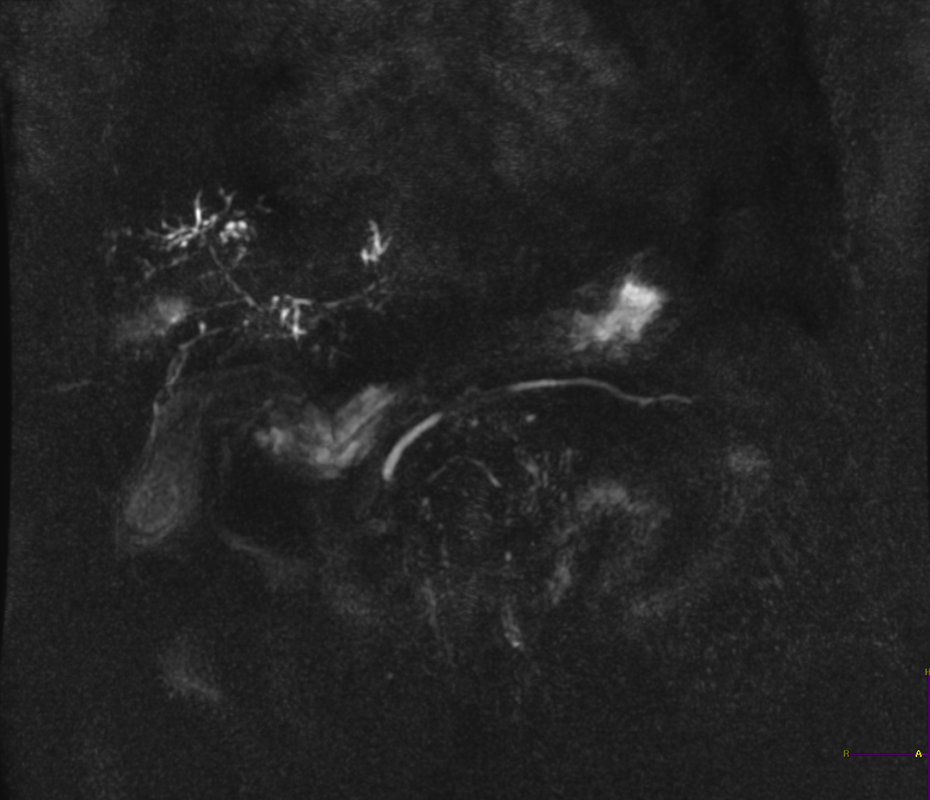

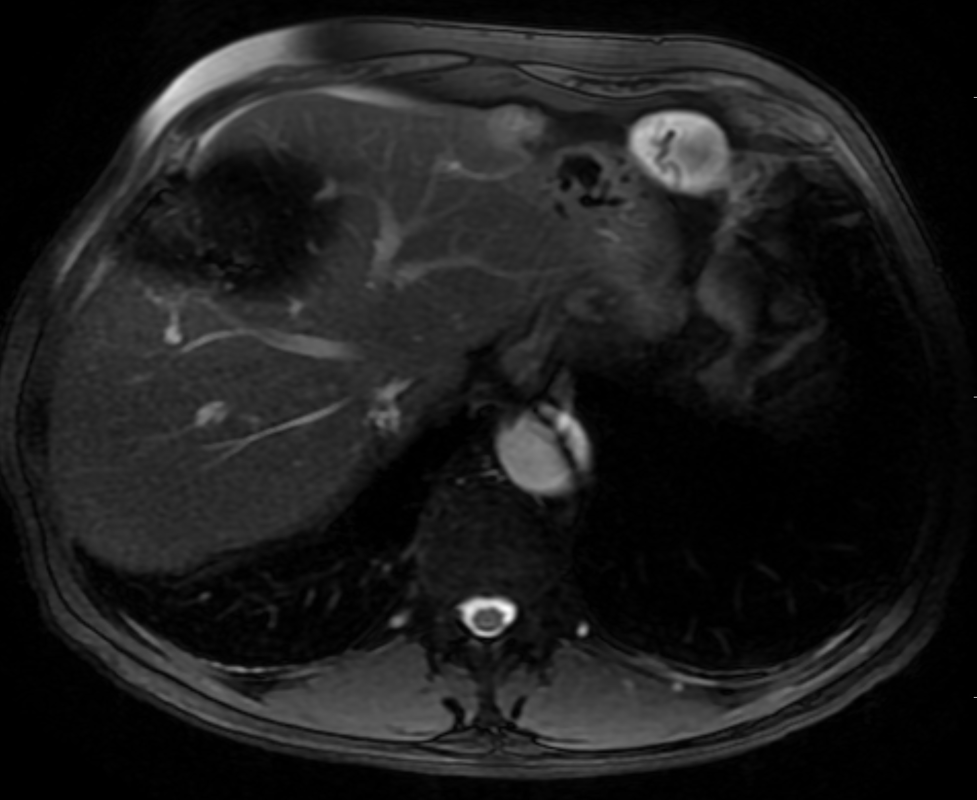

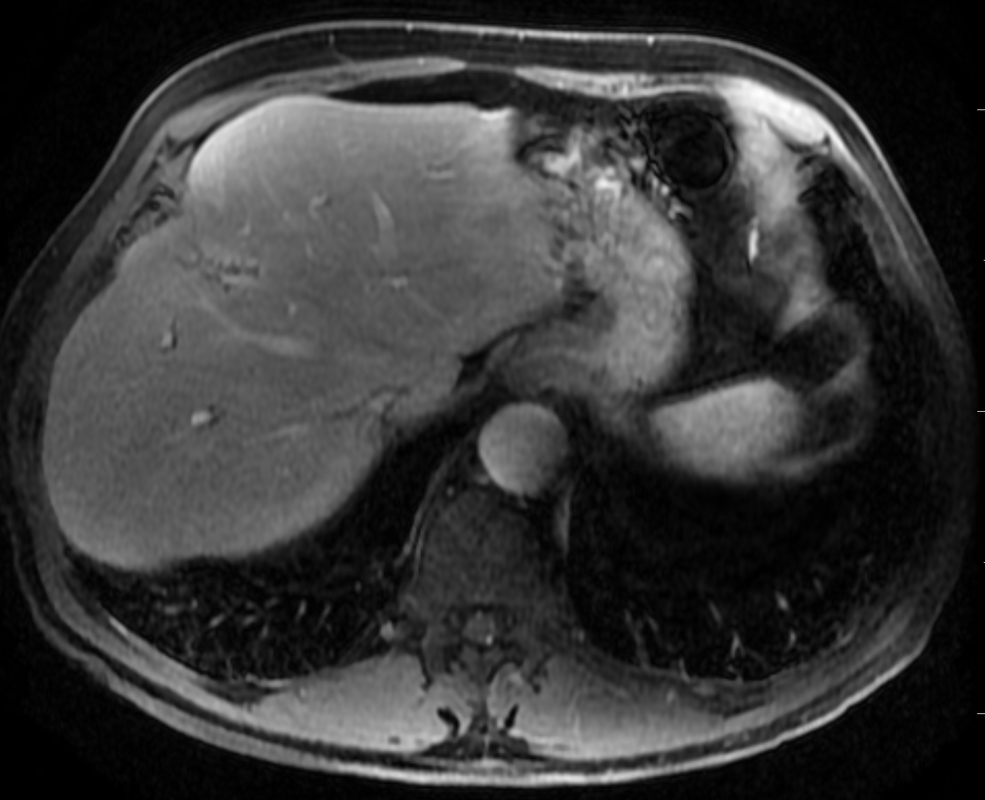

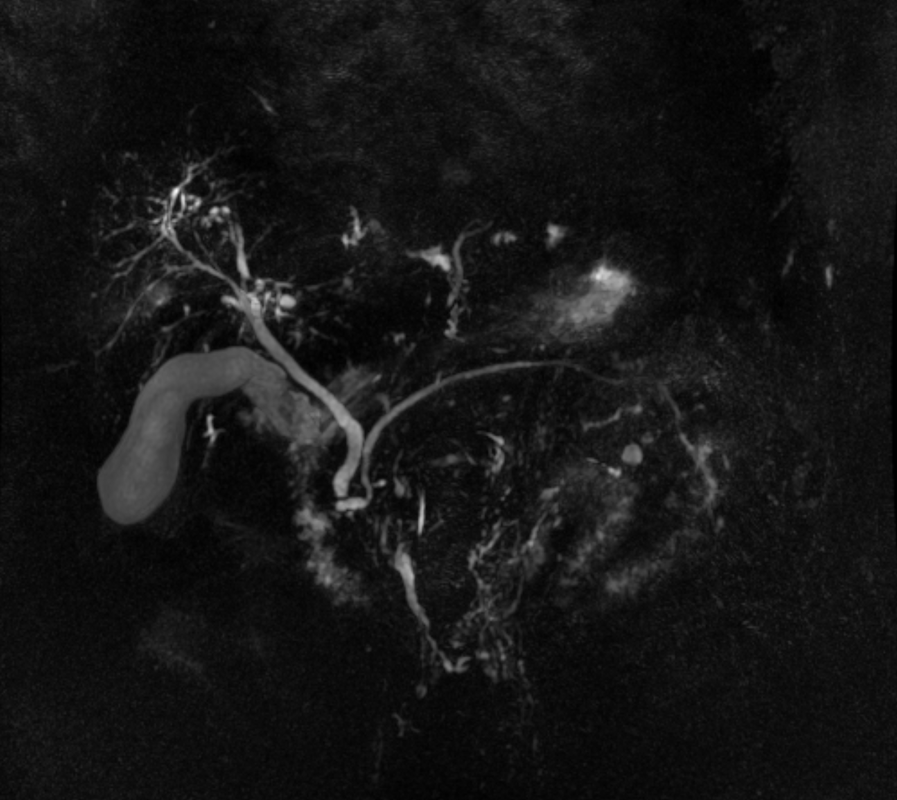

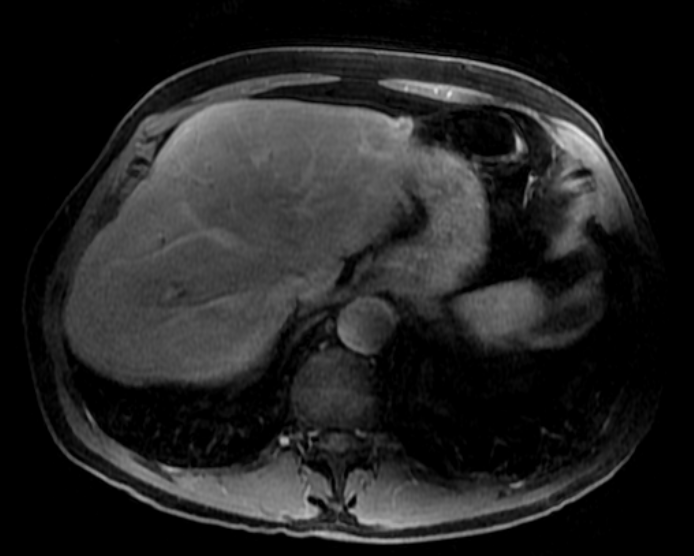

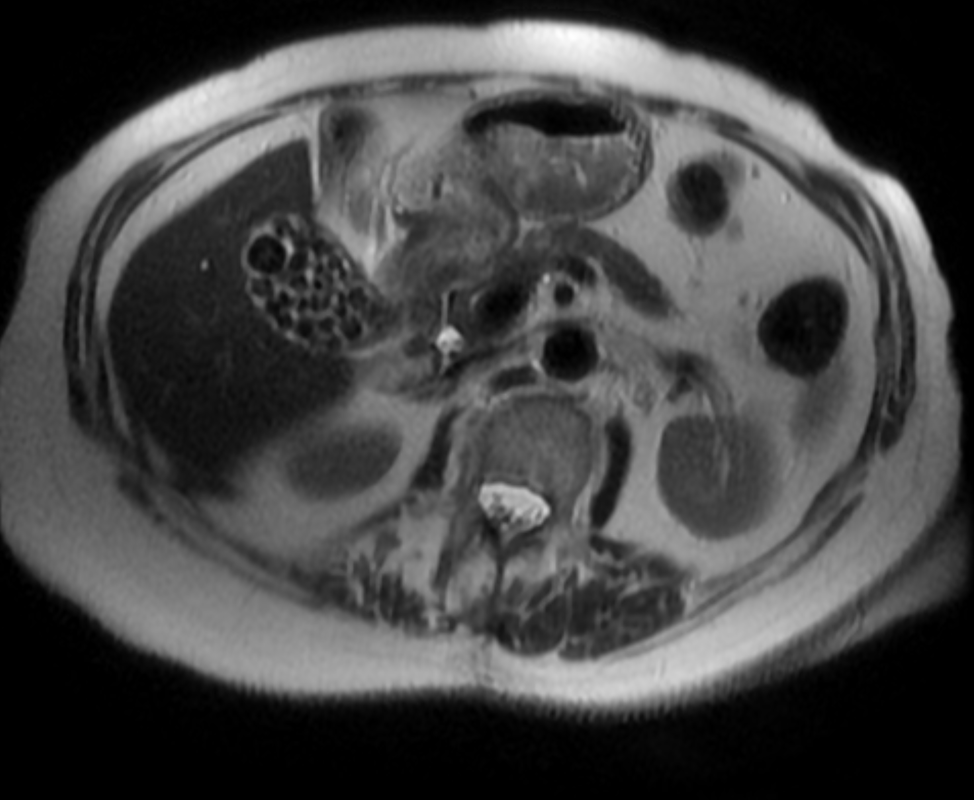

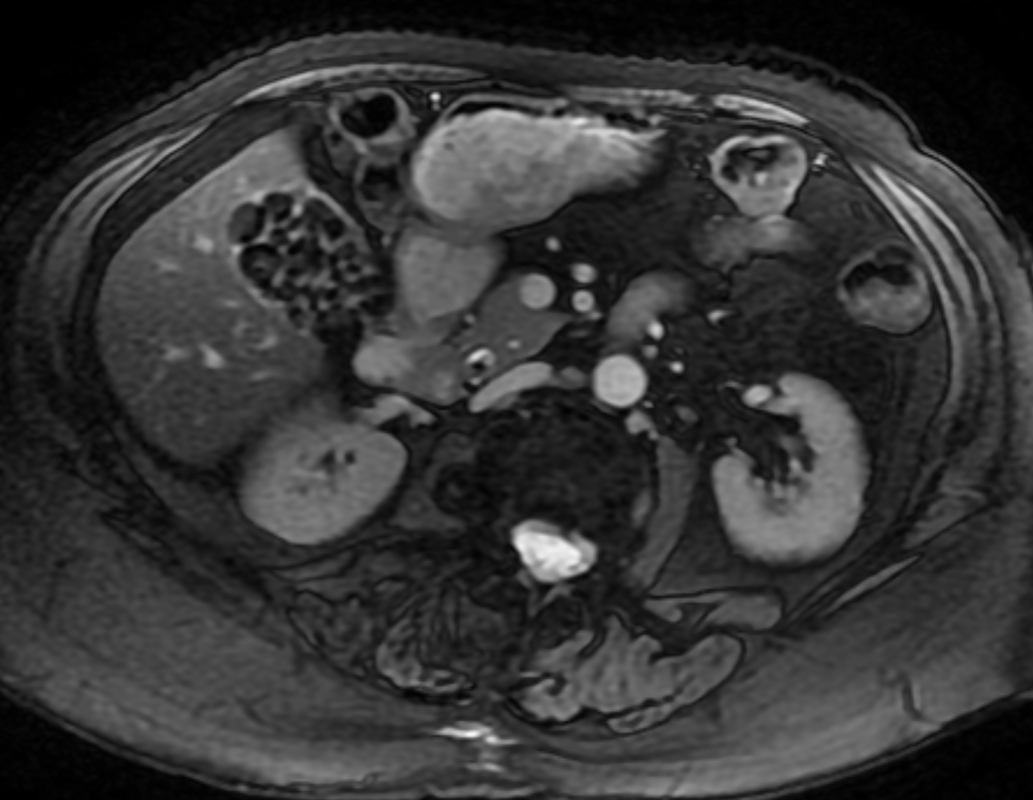

A much trickier case! The images provided from the initial Liver/MRCP examination are a T1 fat suppressed non-contrast image (top left), a FIESTA image (T2 equivalent bright blood sequence, top right), and two post contrast T1 fat suppressed images following intravenous gadolinium (second row). Thin and thick slab heavily T2 weighted MRCP images are provided on the third row. The final row demonstrates a post contrast T1 weighted fat suppressed image at 3 months. The FIESTA image has some degradation due to artefact from the lung parenchymal air affecting the right liver lobe. The original imaging demonstrates a left liver lobe T1 hypointense and heterogenously T2 hyperintense lesion. The lesion demonstrates both peripheral enhancement but also internal extensive reticular enhancement. In addition the contrast enhanced images demonstrate that there is a tubular low T1 abnormality with peripheral enhancement in the central right liver lobe. The MRCP images demonstrate that there are normal appearances of the gallbladder, common bile duct and pancreatic duct but that the intrahepatic ducts demonstrate small clusters of focal subsegmental duct dilatation. At 3 months, without any reported therapy the lesion has regressed to a smaller nodule of enhancement with some retraction of the liver capsule. The tubular low T1 abnormality and the associated enhancement are less conspicuous. The appearances of the tubular abnormality in conjunction with the MRCP images indicate intrahepatic duct dilatation. However, the intrahepatic duct dilatation is discontinuous and not secondary to any obstructive stones or stricture. One could consider the possibility of primary sclerosing cholangitis, however, no typical beading is demonstrated. Additionally the dilatation demonstrates enhancement. This is a feature that indicates inflammation or possibly infection. What about the enhancing lesion? Well the appearance of this abnormality could indicate a malignant lesion. One could then consider perhaps a case of cholangiocarcinoma with metastases, but again the non-contiguous nature of duct dilatation would not make sense and with regards to the lesion itself it is difficult to believe a malignant lesion regressed with no specific treatment. These appearances and the regression are typical of infectious processes, in particular recurrent pyogenic cholangitis. The focal lesion is termed an inflammatory pseudotumour and often demonstrates this avid and reticular enhancement. Regression can be spontaneous or in response to antibiotics and recurrence of lesions is common. Healing can result in focal scarring as in this case. Recurrent pyogenic cholangitis was previously referred to as oriental cholangiohepatitis and clinically is often associated with recurrent pyogenic episodes, although may be asymptomatic in the elderly. Intrahepatic marked ductal dilatation with intrahepatic duct stones can develop (hepatolithiasis). The stones are typically calcium bilirubinate. Infection of the bile with E Coli, Clonorchis sinensis or Ascaris Lumbricoides has been postulated as a cause. The condition remains more common in the far east although is not limited to that population. Long term complications include cholangiocarcinoma and intraductal papilloma formation. Radiology Level: FRCR, FRCS, MRCP, ABR, EDiR, Radiology Junior + The initial images are from an MRCP (magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography) examination. The images on the left are T2 axial images, the images on the right from a FIESTA sequence (equivalent to FISP/TRUEFISP sequence, T2 predominant-although actually ratio of T2/T1- fat suppressed, bright blood sequence) demonstrating that the gallbladder is completely packed with low signal abnormalities consistent with stones. There is no apparent gallbladder wall thickening, oedema or pericholecystic inflammation. These appearances indicate chronic gallstone disease.

It is important, however, to carefully review the remainder of the biliary tree. Hopefully, on such a review you would have also assessed the common bile duct which can be seen in the head of the pancreas (short narrow). This is mildly dilated but additionally on both the images dependent low signal abnormality can be identified consistent with bile duct stones i.e. choledocholithiasis. The presence of gallstones within the bile duct is an important parameter to indicate prior to laparoscopic surgery to ensure that the duct is cleared. The appearances are very evident on the oblique T2-weighted radial ray projection (left). In this image it is perhaps easy to not see the gallbladder due to the loss of high T2 signal caused by multiple gallstones (long narrow). In this instance the choledocholithiasis is easily appreciated (short narrow). These are also appreciated on coronal SSFSE (single shot fast spin echo) acquired through the gallbladder and the lower biliary tree. In identifying extrahepatic duct choledocholithiasis, particularly single stones, it is important to exclude artefact related to flow. Flow artefacts do appear central and are not consistent whereas choledocholithiasis is typically dependent and reproducible on more than one sequence. A typical site for flow artefacts is also at the crossover of the right hepatic artery over the common hepatic duct near the hepatic duct confluence. Abdominal pain and fever. Trickier! Ignore central hepatic signal void artefact (black) on top right image. Radiology Level: FRCR, FRCS, MRCP, ABR, EDiR, Radiology Challenge ++++ 3 months later

Abdominal pain and fever.

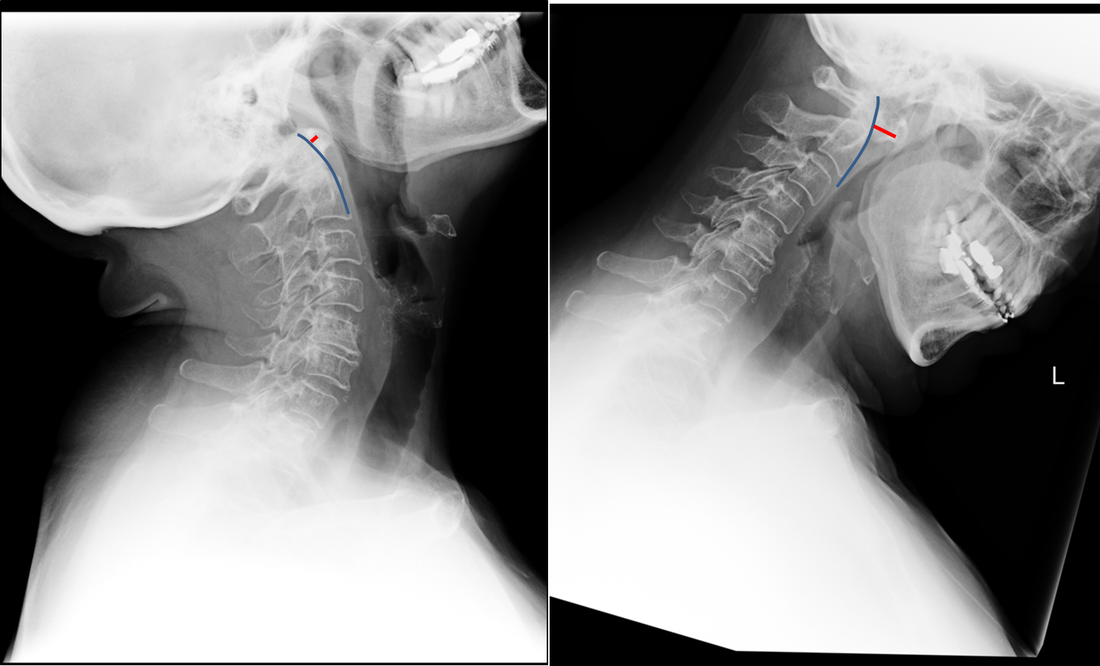

Easy! Careful... Radiology Level: FRCR, FRCS, MRCP, ABR, EDiR, Radiology Junior + Radiology Level: FRCR, FRCS, MRCP, ABR, EDiR, Radiology Junior + The images demonstrate a pair of cervical spine radiographs. The image on the left is in extension the image on the right in flexion. Both images are adequate visualising to C7-T1 or lower. The extension image demonstrates that there is some moderate degenerative change with sclerosis and joint space reduction at C5-C6. The flexion film demonstrates that there is straightening of the cervical spine at this level in flexion. There is, however, no spondylolisthesis (slip).

Looking more carefully at the atlanto (C1) –axial (C2) articulation, we can see that in extension the anterior margin of the dens can be traced superiorly to the skull base (blue line). The predental space (also called atlantodental or predentate space) measures only 2mm (red line). In flexion though the predental space greatly increases to >7mm. The appearances are those of non-traumatic atlanto-axial subluxation/dislocation. In addition there is some loss of clarity of the odontoid peg (confirmed on MRI/CT) suggesting some erosion. These appearances were due to rheumatoid disease. The patient was being assessed pre-operatively. Typically the predental space is usually <=3mm in neutral or extension radiographs, <=5mm in children. In children the ligamentous laxity of the neck in flexion allows some minor increase of this space, but not in adults. The anterior motion of the atlas on the axis/dens is typically restricted by the transverse ligament. The disruption of this ligament can occur by trauma (look for associated fractures or prevertebral soft tissue swelling) or by inflammatory conditions (typically rheumatoid disease but also less commonly psoriasis, Down’s and Morquio’s syndromes, Neurofibromatosis, Osteogenesis Imperfecta). Disruption of the transverse ligament enables atlanto-axial instability. This can be asymptomatic or life-threatening (particularly in trauma). Specifically, posterior translation of the dens can compress the cord resulting in upper motor neuron compressive neurology. Such unexpected spinal compression may become first apparent during intubation and is, therefore, screened for in susceptible patients with rheumatoid arthritis. The condition is termed atlanto-axial instability/subluxation or dislocation and should be differentiated from atlanto-axial rotatory subluxation in which the primary injury is a rotation at C1-C2 that may be associated with unilateral facet dislocation, fractures and nerve root compression with flexed rotated angulated neck malalignment. |

From Grayscale

Latest news about Grayscale Courses, Cases to Ponder and other info Categories

All

Archives

October 2018

|

|

|

Grayscale Courses est. 2015

RSS Feed

RSS Feed