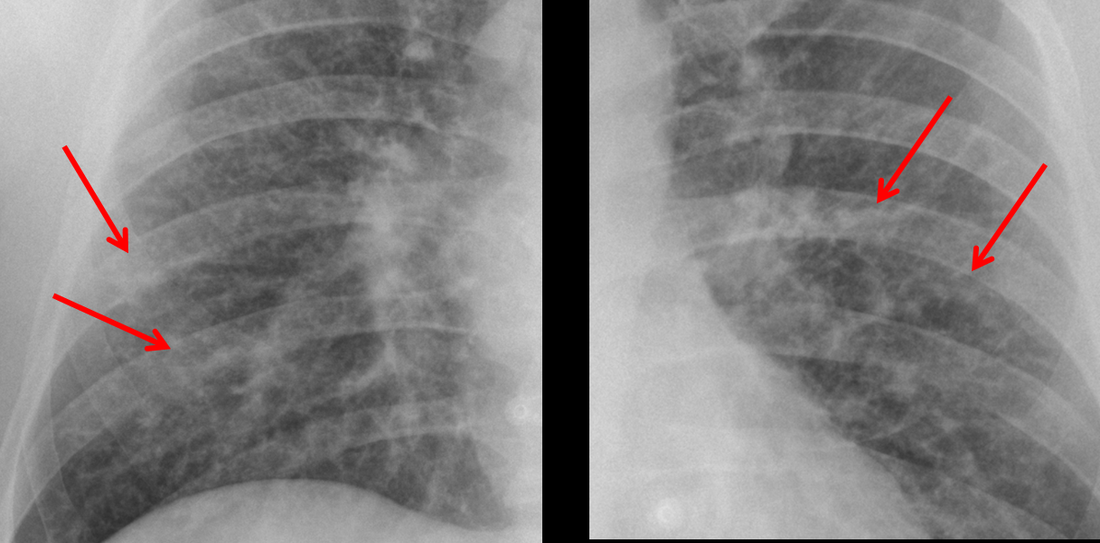

Determining whether an interstitial process is nodular (e.g. miliary), reticular (e.g. fibrotic or oedema) or reticulonodular is critical to determining the cause of pathology and does take some experience. If you saw the nodules but thought this might be miliary nodules in an Asian patient (i.e. perhaps TB), not bad, but miliary is a haematogenous process and should be worst at the bases. For trainees, especially in exams, this is stressful and it is a common situation for trainees to plump for reticulonodular as a compromise where they feel they are not going to be too wrong either way. This is a bad approach. Determining whether the disease is one of these three options helps you to determine the cause. Don’t chicken out of making that decision! In this case reticulonodular meant to me when I was reporting these plain films that I was effectively down to only 2-3 diagnoses, which we will come to.

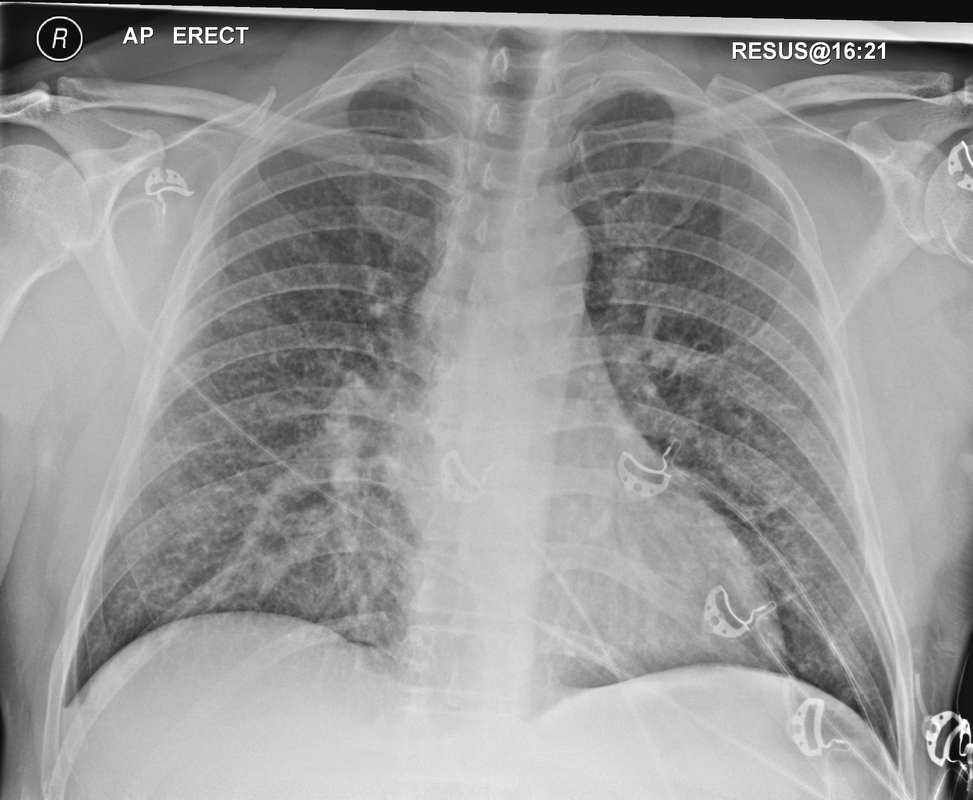

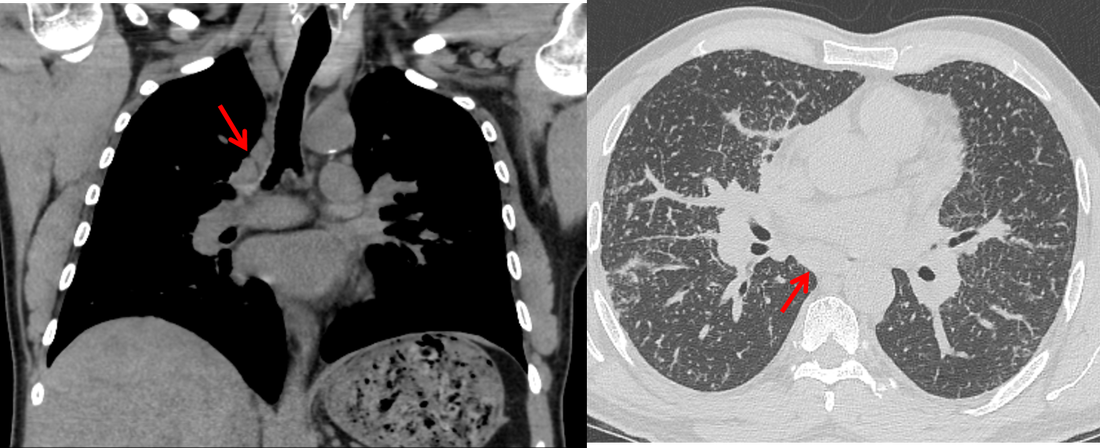

What else on the second chest radiograph? Well the right paratracheal stripe is widened at its inferior margin and the right superior retrocardiac region where the azygo-esophageal stripe should be visible is widened (short arrows). In the tracheobronchial groove the right paratracheal widening could be due to a prominent azygos due to fluid overload/oedema, but the right retrocardiac/azygoesopahageal widening confirmed adenopathy. I was now down to effective one diagnosis. I didn’t have old reference films so I requested a CT with HRCT imaging to confirm my suspicion.

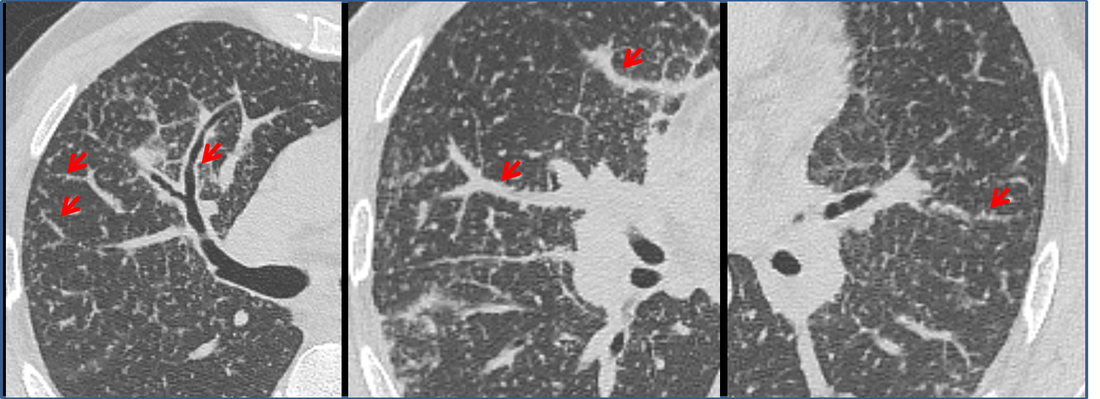

How do I narrow it down? Well lymphangitis is more often unilateral or asymmetric. Interlobular septal thickening is far more common, effusions are very common. Neither are present in this case. So I am left with sarcoidosis or silicosis. I could go and find out if the patient had an occupational exposure, but I am a radiologist and need to push the diagnosis from imaging and clinical knowledge. Firstly silicosis is increasingly rare unless I am in a mining/sandblasting community. Nodes are more likely to calcify in silicosis, although could be non-calcified in both entities. But more importantly this person presented with atrial fibrillation with interstitial oedema at a young age. Silicosis does not cause cardiac disease. Sarcoidosis itself does not usually result in effusions. However, when in sarcoidosis you see evidence of arrhythmia, effusions or oedema, always think about the subset of sarcoid patients who have additional cardiac sarcoid.

The diagnosis in this case was indeed sarcoidosis with pleuroparenchymal and cardiac involvement. I made the diagnosis based on the two chest x-rays but it was academically gratifying to follow through to see the CT imaging and make an illustrative teaching case. Maybe at another time we will look at the next investigation that should follow, a cardiac MRI to confirm myocardial sarcoidosis.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed